Southwark Cathedral Society of Bellringers

Established 1911, Reconstituted 1952 & 1977

President: The Dean, The Very Rev’d Mark Oakley

Charles Dickens at Southwark

In January 1869, Charles Dickens attended a meeting of the Ancient Society of College Youths and ringing practice at St Saviour’s. The following extracts are from the account of his visit published in “All the Year Round” for February 27th, 1869.

The portion of the church we have to pass through is dim enough by what little light comes from the organ loft, where the organist is practising. The lantern we have with us is rather more useful, however, when we reach the narrow winding staircase leading to the belfry, which is dark indeed, and very long and steep. When we reach the first halting-place, we feel but weak about the knees and giddy about the head, and are glad to cross along the level flooring to the loft.

“We nearly had an accident here the other day. Some of the boys were on in front and we were going to cross in the dark. Fortunately I called to them to wait until I brought the lantern, thinking it just possible some of the traps were open. Sure enough they were, and somebody must have gone right down to the floor of the church if I hadn’t sung out in time.” Thus our conductor, to the derangement of our nervous system, for the floor appears to be all trap, and the fastenings may or may not be all secure.

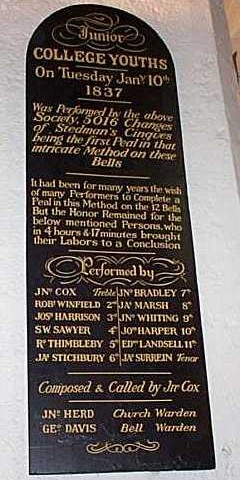

Another spell of steep winding staircase, and we emerge breathless in the ringers’ room. Large and lofty is the ringers’ room, lighted by a gas apparatus, rather like the hoop that serves for a chandelier in a travelling circus. The walls are adorned by large black and gold frames, looking at first sight like monumental tablets to the memory of departed ringers, but proving on further examination, to refer, like the records in the clubroom, but on a larger scale, to the performances of the Society. Peals of all kinds appear to have been rung on these bells; but on one occasion it seems that “the company achieved a true peal of Kent Treble Bob Maximus”. Bob Major we have heard of, but Bob Maximus! Will they introduce us to Bob Maximus tonight?

The ropes of the twelve bells pass through holes in the ceiling, and reach the floor. Under each is a little raised platform for the ringer to stand on, with a strap for his foot to help him in getting a good purchase and each rope half way up is covered by some four feet by a fluffy, woolly looking covering, technically called a “sally” and intended to afford a good hold to the ringer as he checks his bell in the pull down. The case of the church clock fills up one side of the room, and from it unearthly clickings and wheezings presently come as the clock strives in vain to strike. To strike a vibrating bell suddenly from a fresh quarter is to crack it, so when the bells are rung their connection with the clock has to be temporarily severed.

The ropes of the twelve bells pass through holes in the ceiling, and reach the floor. Under each is a little raised platform for the ringer to stand on, with a strap for his foot to help him in getting a good purchase and each rope half way up is covered by some four feet by a fluffy, woolly looking covering, technically called a “sally” and intended to afford a good hold to the ringer as he checks his bell in the pull down. The case of the church clock fills up one side of the room, and from it unearthly clickings and wheezings presently come as the clock strives in vain to strike. To strike a vibrating bell suddenly from a fresh quarter is to crack it, so when the bells are rung their connection with the clock has to be temporarily severed.

Coats are taken off, sleeves are turned up and business is evidently about to begin. But nothing connected, however remotely, with music can be done without a quantity of tuning or other preliminary performances, and change-ringing is no exception to this rule. Before the ring can begin it is necessary to “set” the bells: to set a bell is to get it on the right balance, mouth upward. Some of the bells are set already, some consent to set with a little trouble; but the tenor, a small plaything of 52 cwt, or thereabouts, is obstinate tonight. Three Youths take him in hand, and presently his deep note booms out sonorously, but he absolutely declines to assume the required position. We take the opportunity, and go up, preceded by our friend with the lantern, into the belfry among the bells. As we go, the tenor’s voice becomes louder and louder, and the ladder and walls shake more and more, until at last, as we are going to step onto the platform of the bells, we shrink back as from a blow, from the stunning clash of sound with which he greets us. He is rather an alarming object to behold, swinging violently to and fro close to us, and we decline the invitation to step past him onto the staging beyond, for which feat there seems to us but scant space. Our conductor does not disturb himself in the least, but is presently busy among the bells with his lantern, tightening a rope here, looking after a wheel there, sublimely indifferent to the clanging monster so close to him. All at once, alarming tenor comes up slowly, hovers, poses for a moment as though hesitating, and sets; his great mouth, five feet or so in diameter, turned at last the right way. All his companions have been in this position for some time, and now ringing can begin.

So, after feeling the thickness of tenor’s sides and sounding him with our knuckles, we descend to the floor below, where we find ten ringers ready. A glance round from the conductor, who, with two assistants, rings the tenor, “go”, and they start. The tower rocks, the bells clash, tenor booms at appointed intervals, after some little time, one gets used to the noise, which is not so great as might be expected and begins to pick out the rhythm of the chime. The ringers all have an earnest, fixed expression; attention is written on every face. Occasionally, a slight wandering look betokens that a ringer is a little vague as to his place in the change, but he soon seems to pick it up and come right again. The work is severe, especially on the arms and muscles of the back, but is done with an ease derived from long practice.

The rope is pulled down at the sally, and it falls in a loop to the floor; as it begins to fly up again, the ringer checks it, the bell is balanced against a wooden stay, which prevents it falling over, and the clapper falls; then he lets it run up, round goes the wheel above, and with it the bell, and presently the bells’ mouth comes up on the other side, and the clapper sounds again. It is a delicate operation, checking the bell on its poise: if done too late, the bell breaks away the restraining stay, the rope flies up and probably disappears through the hole in the ceiling, drawn up by the revolving wheel, and disgrace is the portion of that Youth. Disgrace and pecuniary penalty, for a fine is inflicted for a broken stay.

The rope is pulled down at the sally, and it falls in a loop to the floor; as it begins to fly up again, the ringer checks it, the bell is balanced against a wooden stay, which prevents it falling over, and the clapper falls; then he lets it run up, round goes the wheel above, and with it the bell, and presently the bells’ mouth comes up on the other side, and the clapper sounds again. It is a delicate operation, checking the bell on its poise: if done too late, the bell breaks away the restraining stay, the rope flies up and probably disappears through the hole in the ceiling, drawn up by the revolving wheel, and disgrace is the portion of that Youth. Disgrace and pecuniary penalty, for a fine is inflicted for a broken stay.

We are informed that a touch is being rung, and find on enquiry that anything short of a peal is called a touch. In a touch, the changes are simply rung according to the recognised forms, and when the order of bells comes back to that of the first round, the touch stops. Comparatively few changes can be rung in this way, but there are many ways of introducing a fresh change, by which ringers, instead of pursuing and completing the system in which they began, take up some other combination of bells. The signal for such a change is given by the conductor, who calls “bob” or “single”, upon which the desired change is made, and the touch lengthened. The conductor must necessarily have the whole science of change ringing at his fingers’ ends, and must know exactly how to work his bells. Bobs or singles in the wrong place could upset the whole arrangement, and the bells would get so clubbed that they would probably never get round to their proper order again; and as no good ringer ever thinks of leaving off until that state of things occurs, it is difficult to imagine what would happen. A peal consists of not less than five thousand changes, though many more can be rung, and the arranger of a given combination is said to have composed or invented it. He may, or may not, conduct and call the changes; if he does not, the conductor has to learn the peal of course.

The touch comes to an end. Two of the ringers leave their ropes, and two novices take their places. Two older ringers stand behind them to prompt and keep them straight; but the conductor, who this time has left the weighty tenor and taken a bell easier to handle, has his work cut out for him, and may be heard occasionally admonishing the neophytes in gruff tones.

Half a dozen boys have found their way up into the tower, and gaze at the performers with eager eyes; probably looking forward to the happy days when they too will be ringers. The audience has also gradually increased by the advent of stray Collegians, until the room is now pretty full.

A second touch being brought to a harmonious conclusion, the two smallest bells, hitherto idle, are brought into play, the treble sounding after the tenor, like a good-sized dinner bell, and a third and last touch is rung with great spirit. Then after we have received and modestly declined a polite invitation to try our hand at a bell, we file down the corkscrew stairs, not without an uncomfortable feeling that if we were to slip or stumble, an avalanche of College Youths is behind, certain to be precipitated onto our prostrate body. Reaching the chapel again without damage, though with a good deal of dust and damp on our coats from the walls of the staircase, we find the organist still at work (we wonder how he likes the bells ringing overhead while he is practising), and passing over the stone that marks Massinger’s last resting place, emerge into the churchyard. Thence, pursued by a triumphant burst of sound from the organ as if the organist were glad to get rid of us, we troop off to the meeting place of the Society at the King’s Head.